The debate surrounding the new parliament building in New Delhi has largely focused on architectural and financial concerns, with little attention given to its long-term impact on Indian politics and the idea of people’s representation. While critics from non-BJP parties, liberal intellectuals, artists, and town planners have raised questions about the project’s cost and placement, the Modi-led BJP government has defended it on economic grounds.

To understand the implications of the new parliament building, two key issues must be considered: the nature of India’s constitutional democracy and the realities of postcolonial politics of parliamentary representation.

The Indian Constitution places great importance on people’s representation, considering the people as the true sovereign. Article 81 outlines the composition of the Lok Sabha, stating that the number of Members of Parliament (MPs) should be determined based on the population of each state and union territory. As the country’s population continues to grow, the argument for an expanded parliament building to accommodate the increasing number of MPs holds merit in terms of people’s representation.

Additionally, the Constitution provides a flexible framework for adapting to changing political demands. Parliament, as the most representative and accountable legislative body, has the power to restructure and amend institutions in line with the democratic spirit of the Constitution. The initiative to construct a new parliament building aligns with this constitutional feature and can be seen as an extension of the conversion of the Imperial Legislative Council building into the Parliament House in the 1950s.

The number of MPs in Lok Sabha has varied over the years, with the reorganization of states in 1956 significantly impacting its composition. However, in 1976, during the Emergency, the number of Lok Sabha seats was fixed through the 42nd Amendment Act. Subsequent governments did not revisit this decision, even though it limited the scope for people’s representation. The present strength of Lok Sabha stands at 543 MPs, based on the 42nd Amendment.

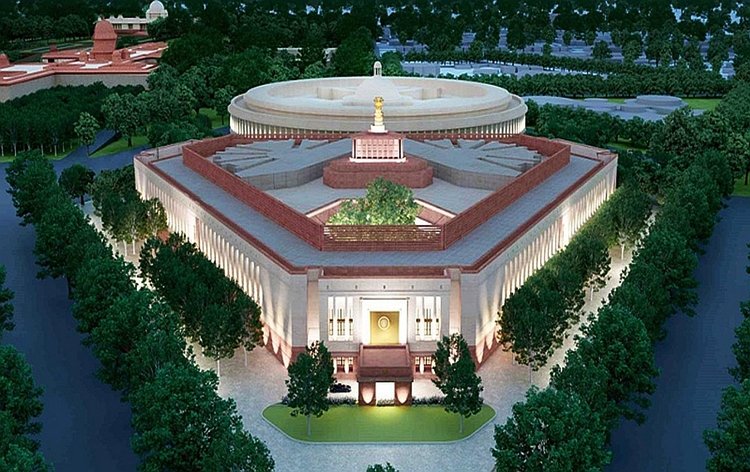

From a technical perspective, the new parliament building does provide space for accommodating more MPs. However, the project’s justification does not explicitly address the democratic aspirations of the people. While the official website cites technical and economic reasons for the initiative, there is no mention of the constitutional mandate or people’s representation.

Unless the new parliament building challenges the status quo and addresses the political class’s attitude toward people’s representation, it will be remembered merely as a symbolic act. It is crucial to go beyond the debate surrounding the 2024 election and consider the long-term impact of the building on Indian democracy and the ideals of people’s representation.